Politics

For all the rhetoric about cognitive abilities, it’s not clear than raw intelligence is the most important factor in a successful executive.

William F. Buckley famously quipped that he “would rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the 2,000 people on the faculty of Harvard University.” This attitude is still commonplace among conservatives today. I recognize that when those on the political right address me as “Professor,” it is not an unambiguous honorific. At least in the realm of politics, many conservatives believe that “the people” possess a more relevant wisdom than “intellectuals.”

By contrast, liberals have for decades touted the intellectual brilliance of their leaders. The Internet is festooned with articles that purport to calculate the IQs of American presidents. The Left’s icons are hailed as geniuses and the Right’s lucky to be able to tie their own shoes. Most of these reports are no better than urban legends, but one study purported to give academic respectability to the claim that liberal presidents had higher IQs than conservative ones.

Neither conservatives nor liberals are consistent in their attitudes towards IQ tests. Despite their fawning over Clinton’s and JFK’s imaginary IQ’s, liberals regularly lament racial discrepancies on tests involving cognitive aptitude. The recalcitrance of those differences has fueled liberals’ skepticism about the validity and fairness of the very concept of IQ. The result has been a widespread push to abandon tests like the SATs as admission requirements to university.

By contrast, many on the political right are open to the claim that IQ is a fair and accurate predictor of job performance. The repudiation of “g-loaded” tests—that is, tests that measure general intelligence—is criticized as an abandonment of meritocracy. But if IQ predicts performance as a lawyer or chemist, would it not also be valuable in a president?

Donald Trump broke the presidential mold in many ways and not least in his outspoken enthusiasm for IQ generally and his own specifically. Throughout his presidency, he celebrated his camaraderie with what he called “high-IQ” people and his disdain for “low-IQ” sorts. At one point, he sought to resolve a disagreement with Secretary of State Rex Tillerson by taking an IQ test. At the presidential debate weeks ago, he challenged President Joe Biden to a “cognitive test.”

Biden may forever put to rest the Left’s claims to having higher-IQ presidents and to valuing intelligence in its leaders. Other than Harry Truman, who never attended college, no president in over a century compiled a more dismal academic record. He graduated near the bottom of his class at the University of Delaware and 76th in a class of 85 at Syracuse Law School—and that included an episode of plagiarism. The average IQ of a college graduate was traditionally estimated to be about 115. Biden’s record as a student, as well as his subsequent career as a politician, suggest that this is, for him, optimistic.

And then there is the fact that the president is 81 years old. We are often lectured on the “immature brains” of the young, as a prelude to cutting them slack when they murder or pillage or just squander their time watching pornography or scrolling TikTok. Measured by overall fluid intelligence, short-term memory, and raw processing speed, however, the human brain’s peak age is in our 20s or even teens, which explains the early age at which mathematicians traditionally record their greatest triumphs. In the humanities, a range of qualities come into play, and thus the greatest works are composed by individuals in their 30s, 40s, or 50s. There are exceptions (Keats’s Ode to a Grecian Urn, written at the age of 23, and Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, completed at the age of 63), but one strains to find any renowned work of art, philosophy, or literature created after the age of 70. And yes, everyone has an octogenarian Aunt Bertha who can recall phone numbers from decades ago. But no one would confuse Aunt Bertha with Joe Biden.

Kamala Harris, age 59, may be an improvement on the IQ front, but Trump has not abandoned the theme. At a recent Bitcoin conference, after first observing that he was in a room of “high-IQ individuals,” presumably including himself, Trump continued: “I’m running against a low-IQ individual. Her. I’m not even talking about him.” Right-wing pundits have piled on with mockery of Harris’s IQ, rumored to be 105 or 110.

No hard evidence has been provided for these claims. True, Harris failed the bar exam the first time she took it, as did many intelligent people. Those who mock Harris’s alleged IQ need to acknowledge that both of her parents have PhDs, and her father was an economics professor. Even before entering politics, she was a prosecuting attorney for over a decade. Calling a political opponent unintelligent or inarticulate might be fair, but speculation as to her IQ is simply that—speculation.

But what if we could require all political candidates to take a “cognitive test,” as the State of Georgia required candidates to take a drug test three decades ago (a measure that was overturned by the Supreme Court)? If so, would we want a president with a high IQ? Apart from the criticism that IQ is racially and culturally biased, the most common criticism is that it is “just a number.” This is true; the question is whether it is a number that has any predictive value, and if so, of what.

Age (in years) is just a number but if one is predicting how much longer an individual can expect to live, then 5 is a number that means something much different from 55. IQ, too, is just a number, but 100, 115, and 145 mean very different things if predicting whether someone can answer neither, one, or both of these questions correctly:

1) 13 17 -4 21 -25 ?

2) shoe : cobbler :: barrel : ?

One might doubt whether there is any real-world significance to the ability to answer these questions, but everything else being equal, why wouldn’t one prefer, especially in the complex, modern world, a political leader who could answer both questions correctly?

The movie Idiocracy is illuminating. The movie’s premise is that generations of dysgenic reproduction culminate in a human population much dumber than that of the current era. Joe Bauers, a cognitively average man (IQ = 100) from the current era, is brought back to life and quickly identified as having the highest IQ of the time. Apparently unlike the current era, the idiots in Idiocracy recognize that a person with a (relatively) high IQ is an asset to be harnessed. Joe is swept into the White House to assist President Camacho in navigating a perilous situation. Although Joe is initially met with skepticism and even hostility, the people eventually appreciate his superior intelligence, and he is even rewarded by being elected president himself at the end of the movie.

By contrast, the revealed preference of the American electorate today is that high IQ is generally not a relevant criterion in choosing our political leaders. There have been occasions when, by national consensus, high IQ was sought in Washington. In the aftermath of the Challenger disaster, the Nobel-winner and acclaimed physicist Richard Feynman was summoned from California to assist the bureaucrats and politicians. Within a matter of weeks, Feynman had not only unraveled the cause of the disaster but demonstrated it in a science experiment.

But more recently, the performance of experts in responding to COVID is apt to reinforce views, particularly among conservatives, that IQ is a dubious qualification for any political post. Anthony Fauci, who was for many months among the most politically powerful people in America, graduated first in his class at Cornell Medical School.

The fledging state of Israel could have had the highest IQ leader in the history of mankind. After Chaim Weizmann died in 1952, the Israeli Embassy to the United States offered Albert Einstein the presidency. Had Einstein accepted and exercised power, Israel’s future would have been imperiled. His introversion and irreverence were adapted to a career in theoretical physics but would have made him a dreadful political leader. His policy positions included espousal of pacificism, socialism, and world government, and he supported Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party in the 1948 U.S. presidential election. Einstein was a morally serious man, but his oeuvre is tarnished by opinions that are, frankly, embarrassing. In 1929 he opined that Lenin was of the class of men that are the “guardians and restorers of the conscience of humanity.”

Einstein raises the question whether high IQ predicts for the personal characteristics that are advantageous in a political leader. One desirable characteristic is conscientiousness, but multiple studies demonstrate that its correlation with IQ is roughly zero. (Perhaps the highest-IQ person of my acquaintance has almost never held down a job but has grifted on friends and government subsidies for decades.) Charisma is useful in rallying a nation, but high IQ is of little or possibly negative value in this regard. People regard quick and decisive thinkers as charismatic, but high-IQ people are inclined to recognize the contingency of their own positions and the merits of the other side in any contested issue.

IQ is positively correlated with openness, true. But this is not necessarily desirable in a political leader. America benefited from having high-IQ, high-openness leaders such as Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln in moments of great crisis, but a central concern of classical political philosophy is tyranny—that is, the danger posed by leaders who combine ruthless intelligence and a detachment from convention. Hitler and Stalin were both high-IQ and high-openness.

It is also unclear, as Einstein illustrates, that high IQ is positively correlated with the substantive political positions that American conservatives would regard favorably. On the one hand, there is evidence that people with higher IQs tend to hold more socially liberal positions. On the other hand, people with higher IQs tend to support free markets more than the median voter. This may be because higher IQ people tend to self-segregate in the modern world and are more willing than less intelligent people to engage in cooperative interactions, unmediated by government bureaucrats.

Among the political leadership class, however, any correlation between IQ and libertarianism (broadly understood) appears to fritter away. European political leaders are, on average, more academically accomplished than their American counterparts, and probably have higher IQs, but they have nonetheless pursued socialist policies for decades. In recent years, for example, roughly 20 percent of Germany’s Bundestag and over half of its ministers have had PhDs.

If, as in Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem, the human race confronted aliens determined to exterminate us, and only breakthroughs in logic, mathematics, and physics, could save us, then we should seek out the most intelligent people in the world. As a first approximation, scores on IQ tests could be a useful tool in identifying candidates. The higher someone’s IQ, the more suited, at least in theory, the person would be in serving on this humanity-saving enterprise. This would mean putting up with a lot of odd characters, but sometimes society must indulge genius even when it entails a fair bit of grief. This was, in practice, the policy adopted by the U.S. government in selecting scientists, including Feynman, to work on the Manhattan Project.

But to return to Feynman’s contribution at the end of his life, his success in figuring out what caused the Challenger disaster in 1986 was only partly because of his intelligence. As recounted in James Gleick’s biography, when the head of NASA, William Graham, reached out to Feynman to serve on the commission to investigate the disaster, Feynman responded, “You’re ruining my life.” Graham later realized that what Feynman meant was, “You’re using up my very short time.” Feynman had just been diagnosed with a second rare form of cancer. His kidneys were beyond repair.

And yet upon accepting the position, he immediately rallied to the cause. He was part-detective, part-scientist, part-whistleblower. The Chairman of the Challenger Commission was determined to avoid any embarrassment to NASA and obstructed Feynman’s efforts, but he was persistent. His work culminated in the televised experiment that demonstrated the shuttle’s O-rings lost resilience at low temperatures.

Feynman was a brilliant scientist, but there were several NASA engineers who recognized the problem with the O-rings. More impressive is the perseverance and courage that Feynman displayed in his final service to his country. To fixate upon his intelligence, or more specifically his IQ, would truncate him as a man. Feynman himself once suggested that his IQ was not high enough to qualify for the high-IQ organization Mensa (130). This was likely false, but may have been an oblique criticism of people who regard their IQ scores as a substitute for genuine intelligence and life accomplishment. (He did, we should recall, write a book, Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman.)

Despite his frequent self-portrayals as whimsical, Feynman was occasionally willing to engage in public-spirited ventures. In 1964, for example, prompted by his own dismay at his children’s math education, Feynman agreed to serve on California’s State Curriculum Commission. He took the assignment so seriously that he read every elementary school math textbook, an arduous and infuriating task for anyone and surely an agony for a man of his intelligence. He bickered with his fellow members on that Commission, refused to accept bribes from textbook publishers, and resigned after a year. But both in failure then and in success on the Challenger Commission, it was Feynman’s integrity, independence, and discipline—what one may call moral virtues—that were indispensable in making him the impressive man he was.

In Outliers: The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell recapitulates the idea, first proposed by the late Arthur Jensen, of IQ “thresholds.” Gladwell writes that “the relationship between success and IQ work only up to a point.” Above a certain threshold, “having additional IQ points doesn’t seem to translate into any real-world advantage.”

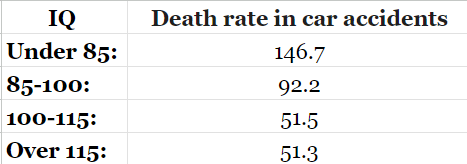

This was not quite Jensen’s argument; in the book Gladwell cites, Jensen proceeds to acknowledge the disproportionate role played in shaping a culture by the “small fraction . . . that is most exceptionally endowed.” But the idea of IQ thresholds is useful in addressing the question posed here: for many tasks, it may be of little or no predictive value above a certain threshold whether someone has an ordinarily above-average IQ or a very high IQ. To give a sense of why, consider the following data, from an Australian article published in 1990:

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

One interpretation of this data is that above an IQ of 100, any increase in IQ does not correlate with a lower or higher incidence of fatal car accidents. One might speculate that a person with a very high IQ is instinctively more cautious but is also more prone to flights of the imagination: the effects wash out.

At least formally, being president might be similar. Above a certain level (perhaps 115) one cannot say that an additional IQ point correlates positively or negatively with being a better president. Presidents with very high IQs might be more variable, given greater rhetorical skills and openness to new ideas, but the average expected performance as president is the same as someone with a lower IQ.

If there is any merit to this hypothesis, we should select presidents who can get the first question right (46). Whether they know the answer to the second question (cooper) might, or might not, be useful, but only if that intelligence is joined to a host of other virtues. And it is on the basis of those qualities and stated policy positions, which cannot be measured or predicted by IQ tests, that voters should cast their ballots.