Foreign Affairs

The late telejournalist was a pioneer of informal diplomacy between American and Soviet citizens.

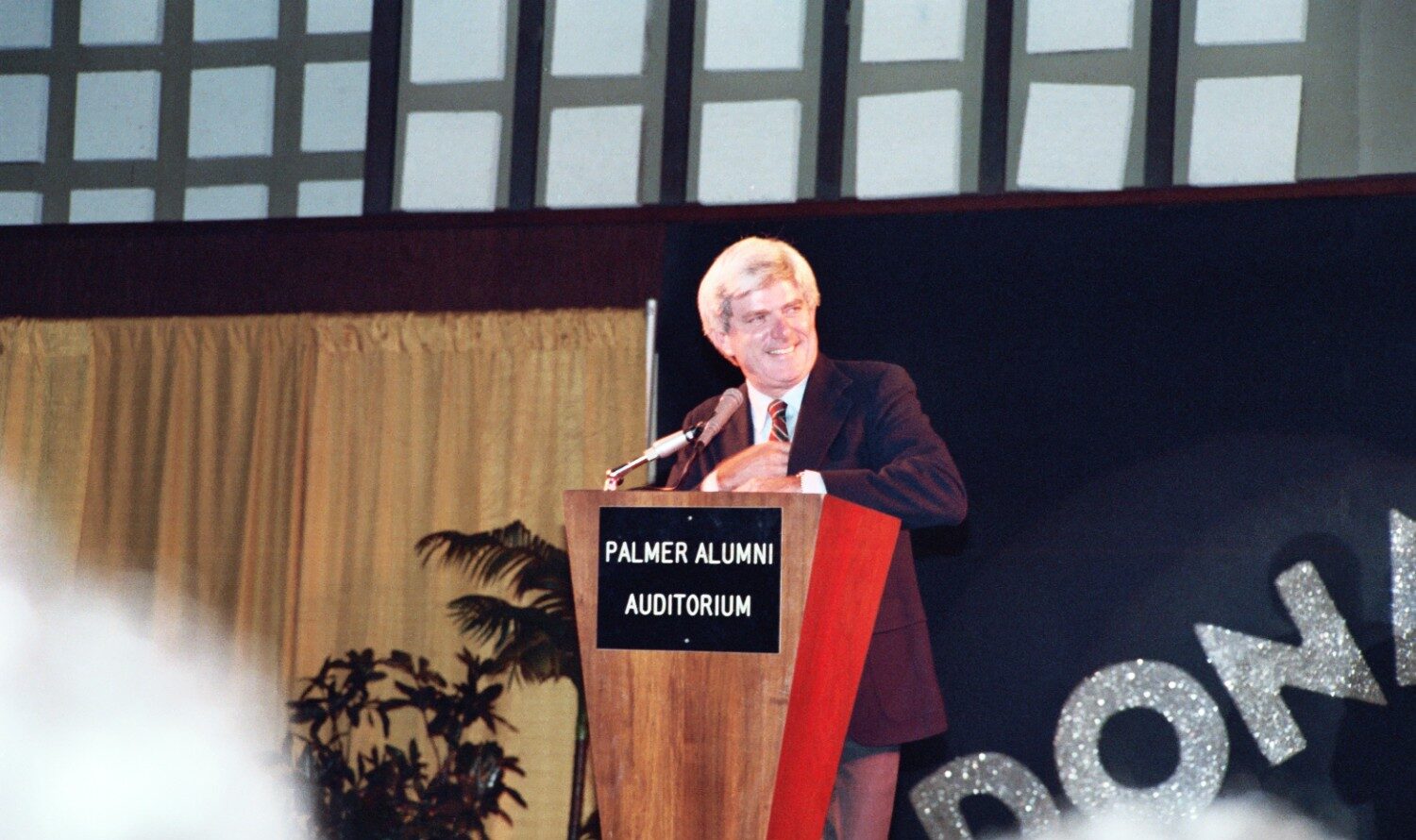

The recent passing of the American journalist Phil Donahue at the age of 88 marked the end of a unique era in television. Revered for pioneering the daytime talk show format, Donahue’s contribution to American media has been well documented. Yet his lesser-known role as an unofficial diplomat, fostering dialogue between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, bears greater relevance today as tensions between the U.S. and Russia once again rise to a boil.

Born on December 21, 1935, in Cleveland, Ohio, Donahue emerged from a middle-class Irish Catholic background to become one of television’s most influential figures. His show, “The Phil Donahue Show,” debuted in November 1967 on WDTN and was groundbreaking for its format. Donahue’s show was the first to integrate audience participation into the talk show genre, allowing viewers to interact with guests and engage in discussions on pressing social issues. This format not only set a new standard for daytime television but also helped shape the careers of future media icons like Oprah Winfrey and Ellen DeGeneres.

Running until 1996 and encompassing over 6,000 episodes, Donahue’s show became a platform for some of the most significant figures of the 20th century, including Muhammad Ali, Jimmy Carter, and Nelson Mandela. His coverage of the 1992 presidential election, featuring a conversation between President George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, further cemented his role as a key player in shaping public discourse. Donahue received numerous accolades for his achievements, including nine Emmy Awards and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which President Joe Biden described as a recognition of his ability to “change hearts and minds through honest and open dialogue.”

While Donahue’s daytime television legacy is indelible, his less publicized role as an unofficial Cold-War diplomat offers the most significant lessons for today’s fractured world. At a time when the U.S. and the Soviet Union were locked in a bitter ideological struggle, with mutual distrust and nuclear arsenals at the ready, Donahue, alongside Soviet-American journalist Vladimir Pozner, took a revolutionary step: He helped humanize the supposed “enemy” by bringing ordinary citizens on both sides of the Iron Curtain together in real-time, televised conversations, known as “space bridges.”

The first of these teleconferences, held in December 1985 and dubbed “A Citizens’ Summit” in the U.S. and “Dialogue through Space” in the USSR, was a historical milestone. Produced by the King Broadcasting Company, the Documentary Guild, and the Soviet State Committee for Television and Radio, this event brought 175 Russians in Leningrad and 175 Americans in Seattle together via satellite for a two-and-a-half-hour discussion. Donahue opened the session with an acknowledgement of the prevailing mistrust, stating, “Not a few Americans believe that you are not really able to speak from your soul for fear of reprisal from Soviet Government authority. There are even some people in this country who feel that you will all serve as mouthpieces for the official party line because to do otherwise might earn you a visit to a psychiatric hospital or perhaps a prison. This is not to say that all Americans believe that.”

The topics of conversation ranged from the war in Afghanistan and human rights abuses to more mundane matters of daily life. Political issues initially dominated the discussion, but as the dialogue evolved, participants began to focus more on personal experiences and shared concerns. One American participant’s plea for a shift away from politics to personal connection captured the essence of these exchanges: “I would like our conversation to be less political so that we could just get to know each other. I think we started off wrong. We started badly! I wouldn’t have come here if I knew there would be so much politics. Can’t you see that you are being provoked from here? I don’t like this! I want to sit down with you and get to know each other.”

The impact of this teleconference was profound. The program was broadcast in prime time on Soviet television, reaching approximately 180 million viewers, while in the United States, where the teleconference was edited down to 40 minutes, it attracted around eight million viewers. This was not merely a television event but a significant step toward humanizing adversaries and fostering mutual understanding. Donahue and Pozner’s initiative was about building bridges between people who had been kept apart by political machinations and ideological rigidity.

Their efforts were not limited to one teleconference. Throughout the mid-1980s, Donahue and Pozner facilitated several more, each with its own unique focus and impact. During the July 1986 teleconference between Leningrad and Boston titled “Women Talk to Women,” in one of the more memorable exchanges, Lyudmila Ivanova, a member of the Soviet Women’s Committee, claimed, “We don’t have sex, and we are categorically against it!” Her remark delivered awkwardly, was meant to highlight the difference in how the Soviet Union and the U.S. depicted sexuality in the media. Instead, it became a moment of shared laughter, symbolizing how an unintended joke could reveal our common humanity even in the Cold War’s thick fog of fear and hostility.

Later the same year, the teleconference “We Wish You Happiness,” held between Moscow and Minnesota, was dedicated to American schoolgirl and goodwill ambassador Samantha Smith, who symbolized youthful hope for peace. Furthermore, also in 1986, Donahue became the first foreign correspondent to report from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster site, further cementing his role as a pioneering figure in international journalism. His coverage of the disaster highlighted not only the scale of the tragedy but also the human stories behind it, reinforcing the idea that despite political differences, people everywhere were bound by everyday concerns.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the very first teleconferences—in 1982, 1983 and 1985— took place without the participation of hosts.

In September 1982, an earlier teleconference marked the beginning of a decade-long practice of remote dialogue between Soviet and American citizens. Initiated during the rock festival “We” and spearheaded by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, it used satellite technology to connect Moscow and California. The festival, aimed at showcasing that “America and Russia can get along,” was a symbolic gesture of cooperation, although it was initially limited to musical exchanges.

The next time the people of the two countries came into contact was on May 28, 1983, two and a half months after U.S. President Ronald Reagan called the USSR an “evil empire.” The teleconference, timed to coincide with Memorial Day, was again held “on the sidelines” of the “We” rock festival, but this time, it focused on the nuclear threat—a pressing concern of the era. Nuclear scientist Evgeny Velikhov’s statement that “people think that nuclear weapons are the muscles of a nation while they are a cancerous tumor on a nation’s body” poignantly captured the shared anxiety about nuclear proliferation. This event underscored the urgency of dialogue in mitigating the risks of a nuclear catastrophe.

The space bridges did not always run smoothly. They faced significant challenges, from technical issues to political tensions. For example, a planned teleconference on the topic of the Moscow Book Fair in September 1983 was due to deteriorating relations after the shooting down of a South Korean airliner, only to gain new momentum two years later, when the 1985 teleconference connecting Moscow and San Diego, commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Second World War, featured Soviet veterans and prominent figures like director Sergei Bondarchuk. The sentiment from Elliott Roosevelt, who remarked that the forum was “a message from the people to the leaders of the two countries,” encapsulated the hopeful spirit of the time.

These space bridges were not merely a product of their time but a bold experiment in media’s potential to bridge international divides. They emerged from a climate of heightened tension, but with perestroika and the ascent of Mikhail Gorbachev, they became emblematic of a new era of openness and dialogue. The connection between Moscow State University and Tufts University in 1989, discussing “The Nuclear Age: Culture and the Bomb,” was one of the last major teleconferences of this format, reflecting the ongoing desire for cross-cultural communication even as the Cold War began to wind down.

Despite the success of these initiatives, the end of the Cold War and the shifting media landscape of the 1990s brought challenges for Donahue. His outspoken opposition to the Gulf War contributed to the decline of his show’s ratings, culminating in its cancellation in 1996. His return to television in 2002 was short-lived, as the MSNBC network terminated Donahue’s new show in 2003, partly due to his critical stance on the Iraq War. Nevertheless, Donahue’s unwavering commitment to his principles, even at the cost of his career, was a testament to his integrity as a journalist and public figure, as evidenced by his 2007 documentary, “Body of War,” which examined the impact of war on American soldiers.

Donahue’s death coincides with a time when the world stands once again on the brink of a new, more dangerous confrontation, this time exacerbated by the ongoing war in Ukraine. NATO is expanding, sanctions are piling up, and the threat of nuclear escalation feels closer than it has in decades. In this context, Donahue’s space bridges seem like a lost relic of a more hopeful time—a reminder that there was once a moment when dialogue was possible, even in the most adversarial relationships.

Today’s media landscape, however, offers little room for the kind of citizen diplomacy that Donahue pioneered. In the 1980s, Soviet leaders jammed American-funded radio programs, but that was seen as a repressive tactic of a closed society. Today, Russia’s media outlets are banned or severely restricted in much of the Western world, and American journalists face increasing hostility in Russia. The opportunity for ordinary Americans and Russians to engage in meaningful conversation has all but vanished. This media blockade in both directions only deepens the Cold War 2.0 mentality.

The recent indictment of Dimitri K. Simes, a prominent political commentator who once advised both Presidents Richard Nixon and Donald Trump, illustrates the complex and often contentious nature of modern U.S.–Russia relations. Simes, whose Virginia home was raided by the FBI and who has faced charges for allegedly helping a Russian broadcaster, Channel One, circumvent U.S. sanctions, exemplifies the challenges of navigating a media landscape fraught with geopolitical tensions. His case highlights the difficulties faced by journalists and commentators striving to bridge divides in an increasingly polarized environment.

It is worth noting that Simes’s name was mentioned more than 100 times in a 2019 report by U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller, which eventually found no collusion with Moscow. Interestingly, the indictments against Simes and his wife came a day after the Biden administration announced a series of actions over Russia’s alleged efforts to influence U.S. public opinion ahead of the general election in November this year.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

As the prominent Russia scholar from the University of Kent in the U.K. and a good friend of mine, Professor Richard Sakwa, rightly pointed out in his 2019 book The Deception: Russiagate and the New Cold War, the current environment is more polarized than even the height of the Reagan-Brezhnev standoff. Sakwa argues that investigations like Russiagate, with their unverified claims and political bias, have deepened divisions within the U.S. and escalated tensions with Russia, making rapprochement nearly impossible.

Despite this atmosphere, Donahue’s legacy serves as both a beacon of hope and a call to action. Imagine, for instance, a space bridge today connecting citizens of Washington and Moscow or Washington and Beijing, allowing them to voice their concerns, share their fears, and—most importantly—recognize their shared humanity. Would it solve all of our problems? Of course not. But it would be a start, and right now, we desperately need a start.

Phil Donahue’s death, in the comfort of his home surrounded by family and his golden retriever, Charlie, was a quiet end for a man whose life was anything but. In a media landscape dominated by noise, polarization, and fear, we need new Donahues. We need new space bridges.