Politics

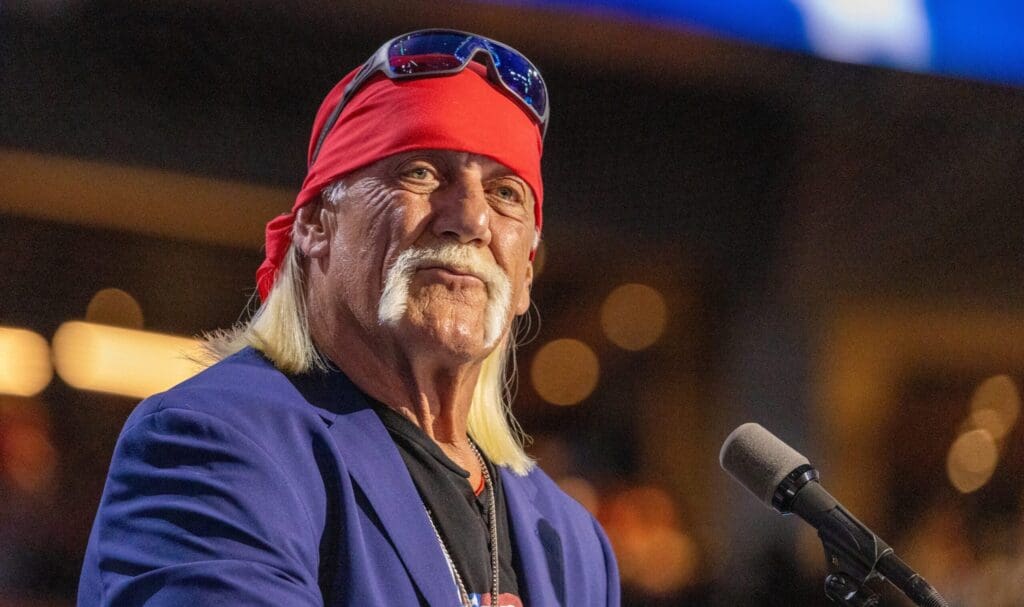

It remains to be seen whether wrestling makes for bad politics.

Support authors and subscribe to content

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.

Login if you have purchased

Politics

It remains to be seen whether wrestling makes for bad politics.

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.