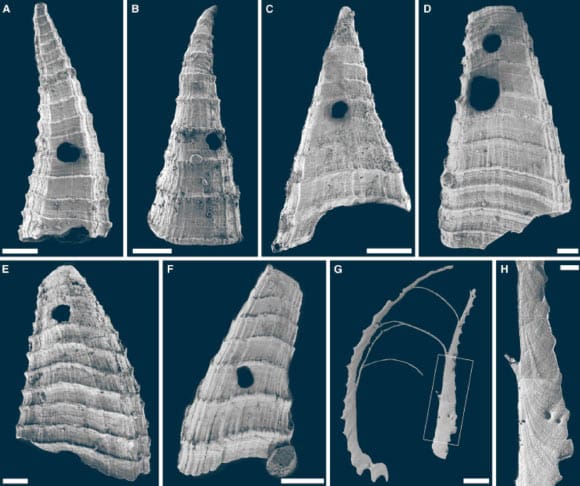

The rapid increase in diversity and abundance of biomineralizing organisms during the Early Cambrian epoch (around 535 million years ago) is often attributed to predation and an evolutionary arms race. A Cambrian arms race is typically discussed on a macroevolutionary scale, particularly in the context of escalation. Despite abundant fossils demonstrating early Cambrian predation, empirical evidence of adaptive responses to predations is lacking. To explore the Cambrian arms race hypothesis, paleontologists from the University of New England, the American Museum of Natural History and Macquarie University assessed a large sample of tiny fossilized shells of the tommotiid species Lapworthella fasciculata from South Australia, over 200 of which show holes made by a perforating predator.

Support authors and subscribe to content

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.