Foreign Affairs

An aggressive display of girl power isn’t going to improve the humanitarian crisis at America’s southern border.

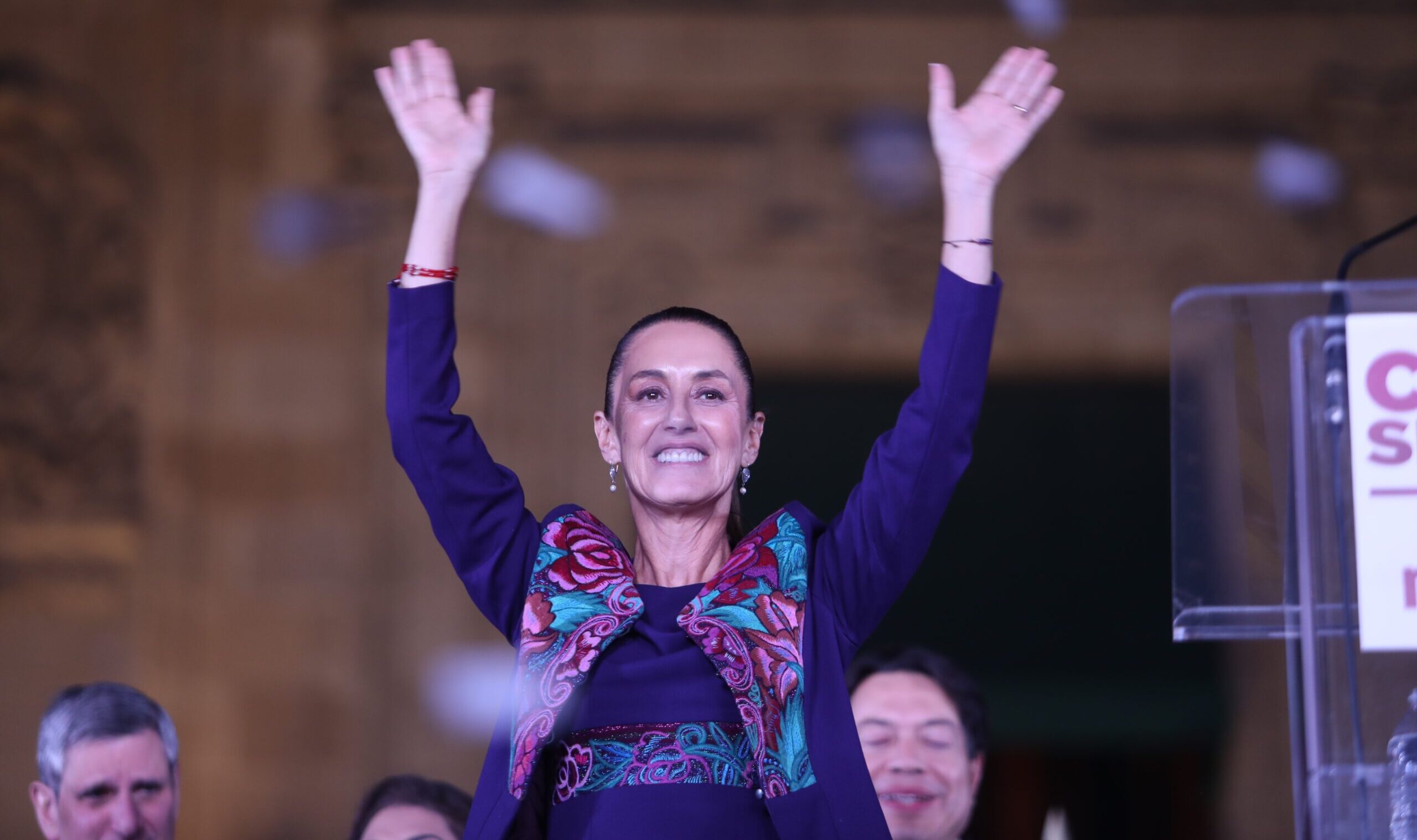

Claudia Sheinbaum will be sworn in as Mexico’s first female president on October 1, just a month before the United States potentially faces the election of its first female president. In many ways, the political careers of Kamala Harris and Claudia Sheinbaum have followed parallel paths. Each highly educated woman cut her teeth on the various agitations familiar to the activist left, namely climate alarmism and women’s liberation. Harris is from San Francisco, Sheinbaum is from Mexico City, both critical seats of their respective countries’ financial and intellectual capital. Both, though under different political circumstances, will inherit and execute the policies of elder statesmen that paved their way to higher office.

If Harris is elected in November, what can we expect of the western hemisphere’s girl-boss duo? There will certainly be breathless celebration from the usual suspects when the two women meet for the first time. If the media’s recent coverage of the Harris-Walz campaign is any indication of the soft-glove approach awaiting the Harris White House, we can expect substanceless adulation over gender to obscure important questions of policy in an era of unprecedented cross-border crime. Since it’s a given that Vogue won’t bother to photograph the women who will be trafficked across the southwestern border in the potential Harris-Sheinbaum era, we’ll have to rely on recent history to forecast the likely human toll of their leadership.

Kamala Harris’ time as the “border czar” has been an unmitigated, measurable catastrophe. Her task, to stabilize the “golden triangle” nations suffering diasporas, failed to the tune of millions of migrants and billions of dollars. Though the Harris campaign is still not providing a platform on their website, we can assume Harris is going to continue the failed “root cause” strategy laid out for her by her aged predecessor.

In Mexico, the “root cause” strategy is better known as the “hugs not bullets” strategy, as laid out by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) during his 2018 campaign for the Mexican presidency. Leading a broad left-wing coalition, AMLO blamed Mexico’s endemic crime problem on economic inequality and proposed a détente with Mexico’s cartels. AMLO invested in everything from infrastructure to children’s youth programs, but critically deescalated Mexico’s response to increasingly capable cartels like the “New Generation” cartel. AMLO’s Guardia Nacional continues to engage with various gangs, but their intensity is a far cry from Felipe Calderon’s offensives of the mid-2000s.

Mexico City’s lenient policies have had predictable consequences. The country set consecutive homicide records in 2019 and 2020 and has endured six straight years with over 30,000 murders annually. Mexico’s investigators and prosecutors, meanwhile, have managed to convict a perpetrator in a dismal 7 percent of homicide cases. This, coupled with record cross-border human trafficking and intensifying inter-cartel combat, highlights the apparent fragility of the Gobierno de la República.

Sheinbaum will inherit Mexico’s perpetual crisis from AMLO, albeit in a stronger political position than Harris will inherit from Biden. AMLO, despite the elevated crime, has tapped Mexico’s substantial oil and gas reserves to deliver steady economic growth and even more impressive long-term projections. It’s this economic promise, as opposed to America’s Biden-era malaise, that fueled Sheinbaum’s 33-point victory in June’s general election. The margin of victory for AMLO and Sheinbaum’s progressive Morena party, built by delivering core economic promises, has forged a new center in the Mexican body politic.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Mexico’s traditional center-right parties didn’t lose the election because of a lack of effort. Mexico’s primary opposition candidate, Xóchitl Gálvez, repeatedly made an issue of Morena’s moral ambivalence and the country’s appalling crime record. Gálvez concluded her unsuccessful campaign by blasting the “hugs not bullets” strategy: “What has been this administration’s strategy? Give the country to organized crime.” Unfortunately, Gálvez’s promise to end “hugs for criminals” didn’t connect with Mexican voters. In a country desensitized by decades of heinous and public displays of gore, center-right criticisms of relaxed law enforcement fell flat.

It remains to be seen if the same ambivalence and desensitization has spread in the United States. Cartel violence, drug trafficking, and human smuggling are slow-burning candles. The frequency and regularity of cartel violence make it challenging for the media and the public to grasp its full extent. The Mexican electorate has made a choice to continue their time-honored national tradition of looking the other way. Some polling, which remains tightly contested, suggests that Americans may be leaning toward a similar decision. In important ways, it’s a choice to realize our Latin American future. Regardless, the decisions made over the course of the next six years in Mexico and the next four years in the United States could cost or save the lives of untold thousands.

Harris and Sheinbaum may bring a new, feminine face to an old crisis, but their choice to continue the failed policies of the past will only continue the chaos that has long haunted their respective countries. Will the American electorate choose to meaningfully address human suffering, or will they allow Vogue to gaslight them into joining Mexico’s exhibition of empty symbolism?